History of the Horse – Eocene 4 – Part 4

|

|

Geschichte des Pferdes – Eozän 4 – Teil 4

|

- Up to now we had in the Eocene an even temperature of about 35 ° C (95° F) around the whole globe – from pole to pole just like on the equator.

Another climate change:

- In the mid period of the Eocene (about 34 million years ago) there began a slow cooling, which also brought seasonal changes, instead of even temperateness. Through these changes deciduous trees developed (which dropped their leaves at colder times), instead of the previously evergreen tropical variations. Those now only remained along the equator in South America, India and Australia.

Now the little Eohippi have to adapt to new circumstances!

- At this time several kinds of primeval horses existed: the Hyracotherium in North America, which we saw in the last Blog, a Propalaeotherium and a Palaeotherium („old animal“) in Europe. The European species however died out again at the beginning of the Oligocene (next Blog!)

|

|

- Bisher hatten wir im Eozän eine gleichmäßige Temperatur von etwa 35 Grad C auf der ganzen Erdkugel – von Pol zu Pol wie am Equator.

Noch mal Klimawandel:

- Im mittleren Eozän (das wäre also etwa vor 34 Millionen Jahren) begann dann aber eine langsame Abkühlung mit einer Entwicklung hin zu Jahreszeiten, anstatt gleichmäßiger Wärme. Durch diese Veränderung entwickelten sich Laubbäume, (deren Blätter in kälteren Zeiten abfielen) anstatt der immergrünen tropischen Varianten. Solche hielten sich nur noch in den Gegenden am Equator in Südamerika, Afrika, Indien und Australien.

Jetzt müssen sich die kleinen Eohippi an neue Umstände anpassen!

- Es gibt mehrere Arten von Urpferden zu dieser Zeit: das schon erwähnte Hyracotherium in Nordamerika, das wir im letzten Blog gesehen haben, ein Propalaeotherium und ein Palaeotherium („altes Tier“) in Europa. Die europäischen Arten starben aber im Oligozän (nächster Blog!) wieder aus.

|

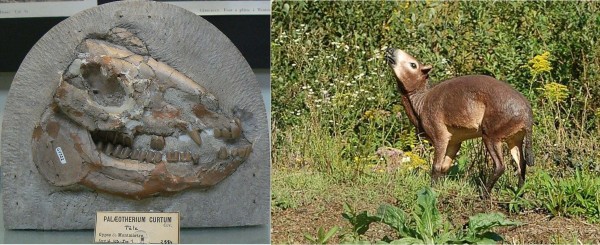

Left: the fossil skull of a Palaeotherium, right: the reconstruction of what a Propalaeotherium might have looked like.

Links: Fossilie eines Palaeotherium Kopfes. Rechts: eine Rekonstruktion, wie ein Propalaeotherium ausgesehen haben mag.

|

Now the mammals are getting bigger!

- All those variations were relatively similar in appearance, though the “old animal” is thought to have possessed a tapir-like short trunk. The larger kinds had a height of about 43 cm at the withers and weighed about 30 kilos. The back was strongly curved upward, so that the highest point lay in the area of the lumbar vertebrae (this is so to this day in tapirs). The neck was quite short, the head position low. The number of vertebrae was similar to today’s, one lumbar less and about three more in the tail (although the number of those can vary even today!)

- The hind limbs ended in three toes, whereof the middle one was the most strongly developed. As with most perissodactyls (animals with an uneven number of toes) the front legs still had an extra smaller fourth toe. Their feet did not yet look like real hooves, rather like blunt nails.

|

|

Jetzt werden die Säugetiere größer!

- Alle ähnelten sich ziemlich im Aussehen, obwohl man denkt, daß das „alte Tier“ ähnlich wie ein Tapir einen kurzen Rüssel besaß. Die größeren hatte eine Widerristhöhe von etwa 43 cm und wogen schon etwa 30 Kilo. Der Rücken war noch stark aufgewölbt, so daß der höchste Punkt im Bereich der Lendenwirbel lag (das hat sich bis heute in den Tapiren erhalten). Der Hals war sehr kurz, die Kopfhaltung tief. Die Anzahl der Wirbel war der heutigen schon sehr ähnlich, ein Lendenwirbel weniger und etwa drei Schwanzwirbel mehr (deren Anzahl aber auch heute noch variieren kann!).

- Die Hinterbeine endeten in je drei Zehen, wobei der mittlere Strahl am kräftigsten ausgeprägt war. Wie bei vielen frühen Unpaarhufern besaßen die Vorderbeine noch einen zusätzlich ausgebildeten, kleineren vierten Zeh. Die Füße sahen noch nicht wie richtige Hufe aus, sondern eher wie stumpfe Nägel.

|

A complete skeleton of a Propalaeotherium from Messel, Germany. This species died out again and is not a fore-runner of the present European horse.

Ein komplettes Skelett eines Propalaeotherium aus der Grube Messel in Deutschland. Dieses Tier starb wieder aus und ist daher kein Vorfahr unserer heutigen europäischen Pferde. |

- By the end of the Eocene continental interiors had begun to dry out, with forests thinning out considerably in some areas. This triggered the evolution of grasses, at first still confined to river banks and lake shores, and not yet expanding into plains and savannas.

|

|

- Zum Ende des Eozäns hin begann das Innere der Kontinente auszutrocknen, und die Wälder lichteten sich in einigen Gegenden beträchtlich. Das wiederum hatte die Entwicklung von Gras zur Folge, zuerst allerdings noch nicht in Steppen, sondern nur entlang der Flüsse und Seen.

|

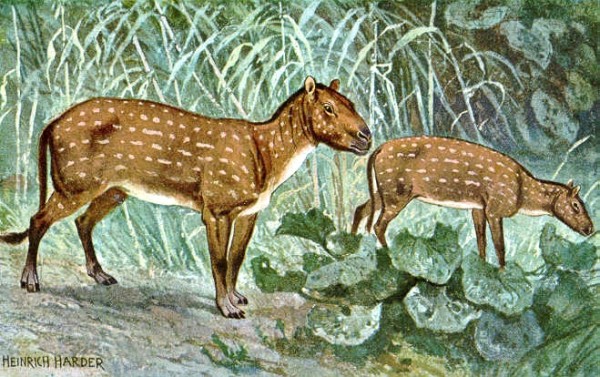

A reconstruction of what a Hyracotherium, the primeval horse of North America, might have looked like.

Eine Rekonstruktion des Hyracotherium, welches sich in Nordamerika entwickelte.

|

Now begins a phase of renewed adaptation:

- The morphology of the entire locomotor system changes. The legs have to become faster, as the little animals increasingly have to look for food in more open landscapes, where it is easier for their predators to detect them.

|

|

Nun kommt eine Phase der neuerlichen Anpassung:

- Die Morphologie des ganzen Bewegungsapparates verändert sich. Die Beine müssen schneller werden, da die Tiere sich nun vermehrt in offene Landstriche wagen müssen, um an ihr Futter zu kommen, wo die Raubtiere sie eher entdecken können.

|

The development of the bones in horses’ legs – from 4 to one single toe.

Die Entwicklung der Beinknochen des Pferdes – von 4 zu einem einzigen Zeh. |

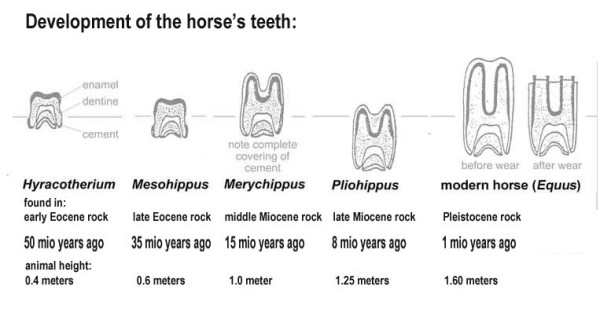

The teeth must get harder!

- The teeth must become harder to be able to chew grass without instantly wearing out. As mentioned before, up to now our Eohippi were eating mainly leaves and fruit, for which their hypsodonte (high-ridged) teeth were strong enough, while now they had to develop harder brachyodont (flat) teeth as grass-eaters.

- Grass contains a high amount of silicic acid and is therefore hard to chew. The development of the necessary more massive chewing musculature later changes the entire shape of the animals’ heads.

|

|

Die Zähne müssen härter werden!

- Die Zähne müssen härter werden, um ohne sofortige Abnützung Gras kauen zu können. Bisher waren die Eohippi ja Laub- und Fruchtfresser mit hochkronigen Backenzähnen, wie wir gesehen haben, während die späteren Grasfresser flache Backenzähne entwickelten.

- Gras enthält einen hohen Anteil an Kieselsäure und ist deshalb hart zu kauen. Die Entwicklung der nötigen massiveren Kaumuskulatur für diese Umstellung verändert mit der Zeit dann die ganze Kopfform der Tiere.

|

The development of the horse’s teeth over time.

Die Entwicklung der Zähne der Urpferde. |

- Onward into the Oligocene – the time of about 34 to 23 million years ago – in which the European sidelines of the primeval horses totally died out again, but the species in North America developed rapidly in interesting ways. What we can call “rapidly”, when talking in millions of years, I guess…

Read on !!!

|

|

- Auf gehts ins Oligozän – die Zeit von vor etwa 34 bis 23 Millionen Jahren – in der die europäischen Arten der Urpferde wieder total aussterben, die Arten in Nordamerika sich aber in interessanter Weise rapide weiterentwickeln. Was man, in Millionen Jahren gezählt, so „rapide“ nennt…

Lesen Sie weiter!

|